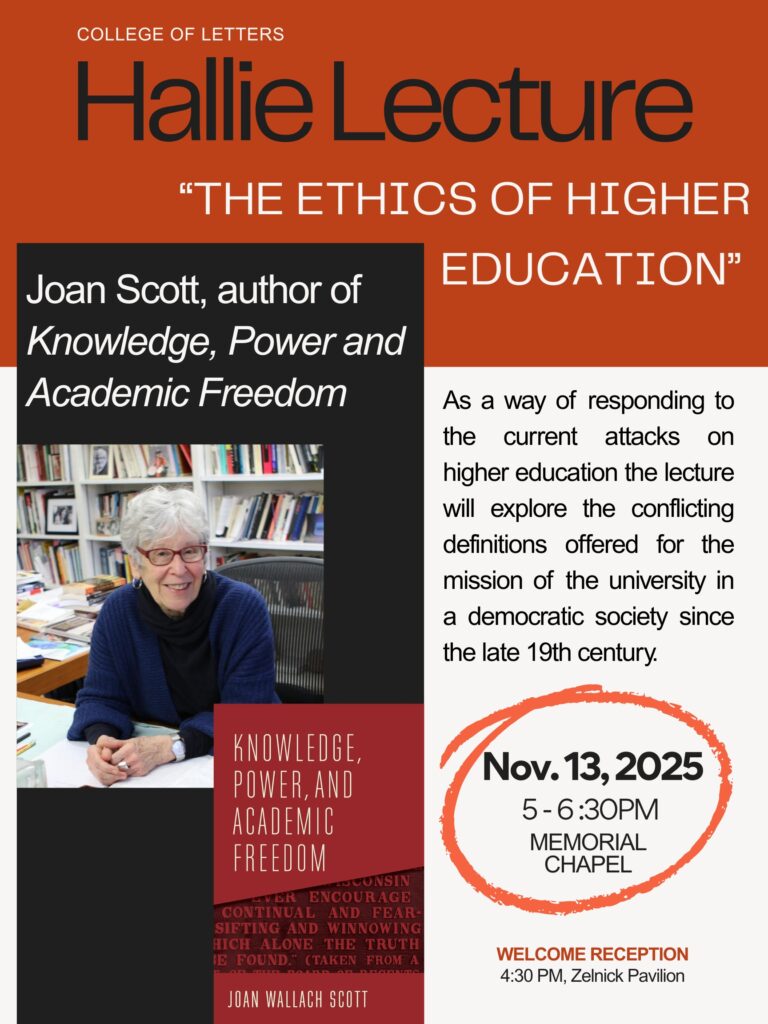

What is the role of higher education in a democratic society? How does that role change in times of academic and political repression? How does one begin to critique universities as spaces for critical thinking as well as corporate institutions? This year marked the 32nd annually held Hallie Lecture sponsored by the College of Letters, with guest speaker Joan W. Scott, author of Knowledge, Power, and Academic Freedom answering those very questions in the current context of attacks on higher education. The lecture was preceded by a Welcome Reception at Zelnick Pavillion.

“What’s always struck me most about Joan Scott’s work and about Joan herself is that ethical seriousness is under us,” Professor Ethan Kleinberg said, in his introduction of Joan Scott at the lecture. “She’s never been content with critique for its own sake. Her scholarship asked us to consider not just what we know, but how and why we know it. To recognize that the pursuit of knowledge should never be separable from questions of justice, responsibility and care. That commitment stands for lifelong defense of academic freedom and the university as a space thereof.”

Among the University’s most significant lecture series, the Hallie lecture honors Phillip Hallie, Professor Emeritus of philosophy and the humanities, and his best known work ‘Lest Innocent blood be Shed’, which explored good, evil, choice, and circumstance in the case of French Huguenot villagers during German occupation in World War II.

Joan Scott began by outlining the challenges facing higher education and democratic society today: from the acquiescence of prestigious universities to federal oversight of curriculum, the elimination of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion practises, the capitulation to Zionist demands that critics of Israel be punished as anti-semites, the failure to protect international students facing visa revocals, to the repression of faculty and student protestors’ free speech.

Joan Scott gave historic examples of higher education institutes compromising on their mission— during the rise of the Nazi Party in Germany in the 1930s, to the ousting of faculty as suspected communists under McCarthyism across the United States in the 1950s. Calling attention to a deal for expanded federal funding that the White House offered nine universities in exchange for implementing educational policies in October, Scott spoke about viewpoint diversity in the classroom.

“It’s no accident that the Compact issued in October seeks to impose viewpoint diversity [in the academy],” Scott said, adding that viewpoint diversity from the authoritarian administration’s point of view assumes that viewpoints are fixed, as the property of individuals whose minds aren’t changed by the influence of education. “Their viewpoint of diversity was a perversion of the university’s mission, an attempt to put political boundaries in the classroom in order to substitute biological inoculation for the ethically driven pursuit of knowledge.”

Speaking to the reality of U.S. universities dealing with these demands, Scott drew a line between mere compliance and ‘negotiating’, finding ways to accommodate demands to avoid the worst repercussions.

Nonetheless, Scott maintained, “The idea that signing on with the fascist then or now is a way of protecting the University is delusional.” Rather, Scott defined the role of the University as ennobling and training democratic citizens. Scott referenced Michel de Certeau’s definition of Ethics, articulated through effective operations, and it defines the distance between ‘what is’ and ‘what ought to be’. The distance signifies a space where we have ‘something to do’.

“I want to argue that higher education takes place in that space,” Scott said. “The ‘something to do’ is the critical work of knowledge production that enables us to get from what is to what ought to be. The ‘what is’ is our present knowledge, its limited ability to address social, political, or intellectual problems, to explain fully the distance between the democratic principles we aspire to and the realities that organize our lives… We don’t know what that ought to be is, but we might get there. ”

Scott then highlighted the importance of ‘critique’ as an impulse of our unquenchable desire to know, an intellectual instrument that refuses to be sated with present reality, training democratic citizens to be critical thinkers.

“So first, desire,” Scott said. “I define the ethics of higher education as the cultivation of a relentless desire to learn more and better than you do now. Education at once unleashes and channels this desire for truth. Study turns one into a student, which is to say someone whose desire is structured by the voluntary assumption of limits unassailable and affable, limits that entail distinctions of true and false.”

This critique can be disruptive too, calling into question ethical values, as well as the interests they might serve. This begged the question: Can critique go too far?

“The scholars who founded the American Association of University Professors in 1915 understood this unsettling to be the mission of a democratic education,” Scott said, dissecting the genealogy of University administrators and faculty engaging in ‘Academic Freedom’ under free speech among its other tenets, as well as responding, reacting and organising when these freedoms were encroached upon.

“In a way perversely, academic freedom was denied to professors with dissident political beliefs. Visited political beliefs in the name of academic freedom, and perversely, yet again, universities carried out the wills of government in the name of academic freedom, that is to prevent interference by politicians and so protect their claim to institutional independence,” Scott said.

Scott spoke about the balancing calculus of a University’s state and corporate interests— when knowledge production shaped federal initiatives, begetting at the same time from federal funding, making the balance of state control and institutional independence difficult to accomplish.

Closing the lecture, Scott clarified once again that what she was offering was a “utopian manifesto”, a set of ideals that challenges the various critiques of universities. Academic freedom is one of those ideals. “My vision of academic freedom harkens back to the progressives and considers that its job is to protect the most diverse of critics, those whose questioning induces vertigo [in] anyone who thinks one is good enough or unalterable. Those who challenge the orthodoxies of their disciplines, the limits of political rule, and accept ideas as unpowerful.”

Attendants asked questions about the current role of the AAUP, the connections drawn between Executive Orders in relation to distorting science and gender, and the methodology of critiquing one’s own values. Attendants, faculty, and Professor Scott then convened for a dinner after the lecture, in the Daniel Family Commons.

Written by COL Major Janhavi Munde, ’27